Major Triads

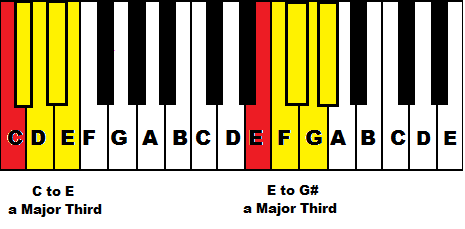

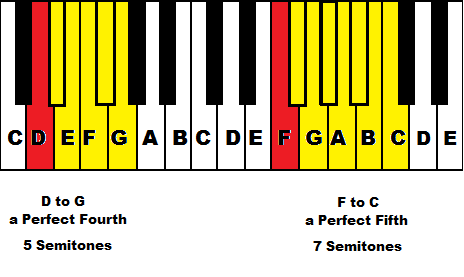

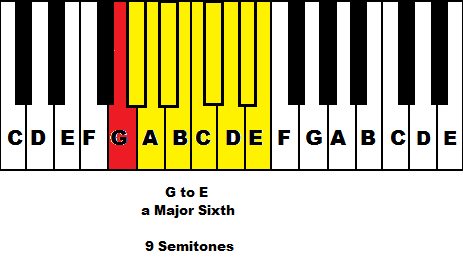

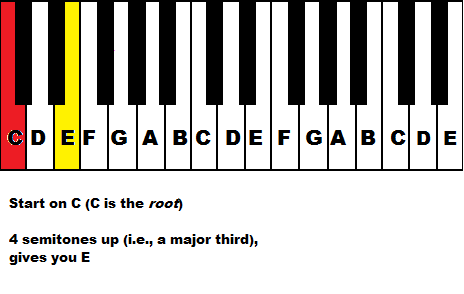

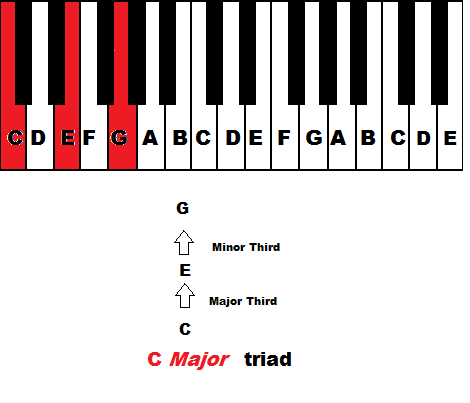

Remember major 3rd and minor 3rd intervals? You better, because those are essentially the foundation of chord structures. To form a major triad on any one note (for example, C), we first go up a major third from the root. C is the root, so going up a major third gives you E

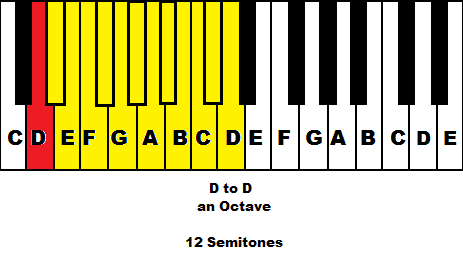

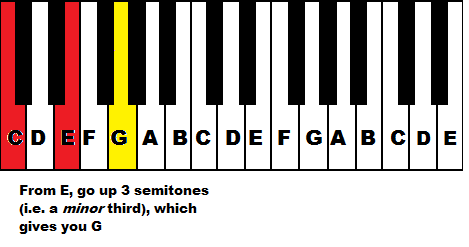

That covers two notes of the triad. To get the last note, start on the second note (the E in this case), and go up a minor third

In conclusion:

As always, I encourage you to play out the notes so you can hear what the chords sound like. You can play multiple notes at one time using this virtual keyboard.

Since I'm such a nice guy, rather than making you figure out each major chord on your own, I'll just list them out. The first note of each triad is the name of the chord (e.g., F A C is an F major triad). Also remember that black keys can have two different note names (e.g., Bb and A# are the same, as is D# and Eb).

C E G

F A C

Bb D F

Eb G Bb

Ab C Eb

Db F Ab

F# A# C#

B D# F#

E G# B

A C# E

D F# A

G B D

________________________________________________________________

Got all that? I hope so. Because now it's time for minor triads!

________________________________________________________________

Minor Triads

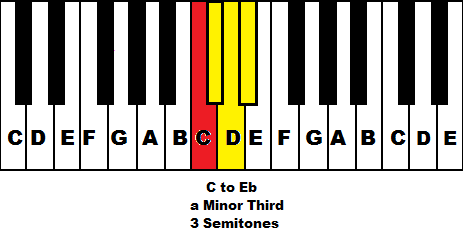

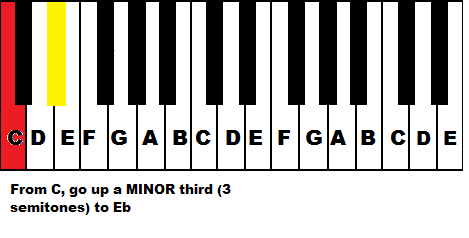

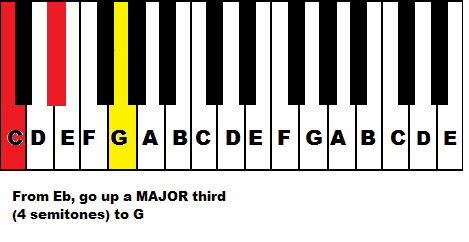

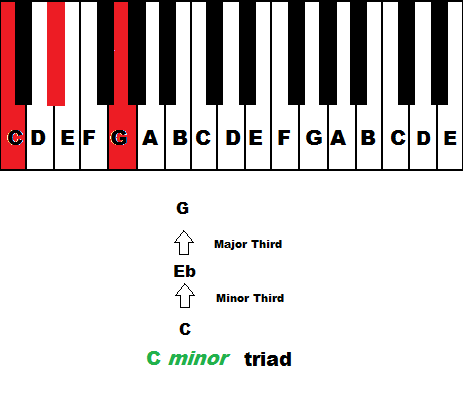

There are a few ways in which you can think about minor triads. The "proper" way is to think about the intervals. Whereas a major triad contains a major third, and THEN a minor, a minor triad is the opposite. A minor triad starts with a minor third and ends with a major third.

In a nutshell:

If you're particularly observant, you might have noticed that 2 out of the 3 notes of a major and minor chord are the same. The root (in this case, C) and the fifth (G) are the same in both major and minor. However, the third is E in a C major triad, but Eb in minor. In other words, the third of a minor chord is one semitone lower than the third of a major. This little trick may help you remember minor chords more easily if you don't want to go through the hassle of calculating those intervals every time.

But for your convenience, I'll list out all of the minor triads just like I did with major:

C Eb G

F Ab C

Bb Db F

Eb Gb Bb

Ab B Eb **

Db E Ab **

F# A C#

B D F#

E G B

A C E

D F A

G Bb D

** Pure music theorists would argue that the proper spellings for these chords should contain Cb instead of B, and Fb instead of E. Ignore them. Just use B and E. It's a lot easier.

Rather than add even more to this excruciatingly long entry, I'll provide an example of how these chords are used in a separate post. Stay tuned!