How about a little Otis Redding? Also bringing back the a cappella!

Monday, July 18, 2011

Friday, July 1, 2011

Lesson #5 - Extracting Chords From a Major Scale

And here we are! The lesson you all (read: I) have been waiting for! Let me just reiterate some keys aspects about chords (specifically, triads) and the major scale before I throw you into the deep end.

Triads

C - D - E - F - G - A - B - C

Scales with flats:

F Major (1 flat)

F - G - A - Bb - C - D - E - F

Bb Major (2 flats)

Bb - C - D - Eb - F - G - A - Bb

Eb Major (3 flats)

Eb - F - G - Ab - Bb - C - D - Eb

Ab Major (4 flats)

Ab - Bb - C - Db - Eb - F - G - Ab

Db Major (5 flats)

Db - Eb - F - Gb - Ab - Bb - C - Db

Scales with sharps:

G Major (1 sharp)

G - A - B - C - D - E - F# - G

D Major (2 sharps)

D - E - F# - G - A - B - C# - D

A Major (3 sharps)

A - B - C# - D - E - F# - G# - A

E Major (4 sharps)

E - F# - G# - A - B - C# - D# - E

B Major (5 sharps)

B - C# - D# - E - F# - G# - A# - B

F# Major (6 sharps)

F# - G# - A# - B - C# - D# - E# - F#

Memorize all of that? Good. Because here comes the fun stuff.

Chords are created from thirds. However, the major scale consists of notes all separated by seconds. C to D is a second, D to E is a second, E to F is a second, and so on. Nevermind whether they are minor or major. Just know that they are all seconds.

C D E F G A B C

SECONDS

Since triads contain three notes separated by thirds, and not seconds, let's find a chord from the C major scale. And to make things easy, let's start on C. So what we do is start with our root (C), skip D, then go to our next note (E), skip the F, and then find our last note (G)

C __ E __ G

C-E-G? Why, that's a C major triad! And we got that by building a chord on the first scale degree. Go ahead, play it yourself (note: You can play the virtual keyboard using your computer keyboard. F and G on the computer play the notes F and G respectively, and everything else lines up accordingly. Try it out for yourself)

So what does this have to do with anything? Why are we making chords from scales? How will that help us play other people's songs or create or own?

Well, the big deal is that most songs with which we are familiar in Western culture are based around one key. That is to say that when an artist writes a song, most if not all of the notes in that song will belong to one key signature. If someone writes a song in the key of G, then probably at least 98% of the notes will be one of the following:

G A B C D E F# G

i.e., the notes of a G major scale.

The thing is, no one wants to hear all of those notes played at the same time. While the sequence of notes in a scale may sound good, playing them simultaneously will sound like garbage. Certain combinations of notes sound great together, and other combinations just suck. So to keep things under control within a song, we have harmony. Simply put, different sections of a song will be based around different chords. But whatever chord it is, it will likely be a chord that's consistent with the key signature. Take a listen to this song medley:

If you listen closely, you'll notice that the chord on the piano changes about every 2 seconds. The chords being played are as followed:

A minor: A - C - E

F major: F - A - C

C major: C - E - G

G major: G - B - D

The only major scale that contains all of these notes is C major. So we can probably assume - nay, I am TELLING YOU - that the songs in this medley are in the key of C!!.

The progression of A minor - F major - C major - G major is a 6-4-1-5 in the key of C. Remember, we created a C major chord by building a chord on the first scale degree of C major (i.e., the first note of the C major scale). That is the 1 in this progression. Let's double-check the others to make sure they're right.

6

What is the sixth scale degree of C major? Let's count up the scale:

C - 1

D - 2

E - 3

F - 4

G - 5

A - 6 BAM!

Now what do we get when we build a triad on that note?

A B C D E

A - C - E

A to C is a minor third. C to E is a major third. Which means the 6 chord of C major is an A minor triad!

4

What is the fourth scale degree of C major? Let's count up the scale:

C - 1

D - 2

E - 3

F - 4 SHAZAM!

Now what do we get when we build a triad on that note?

F G A B C

F - A - C

F to A is a major third. A to C is a minor third. Which means the 4 chord of C major is an F major triad!

5

What is the fifth scale degree of C major? Let's count up the scale:

C - 1

D - 2

E - 3

F - 4

G - 5 BAZINGA!

Now what do we get when we build a triad on that note?

G A B C D

G - B - D

G to B is a major third. B to D is a minor third. Which means the 5 chord of C major is a G major triad!

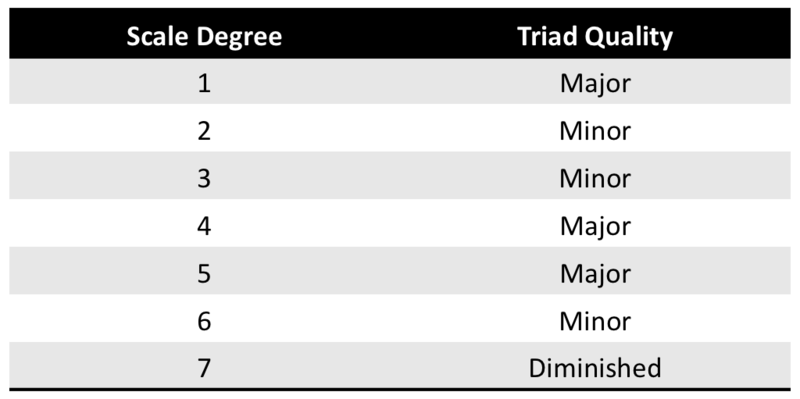

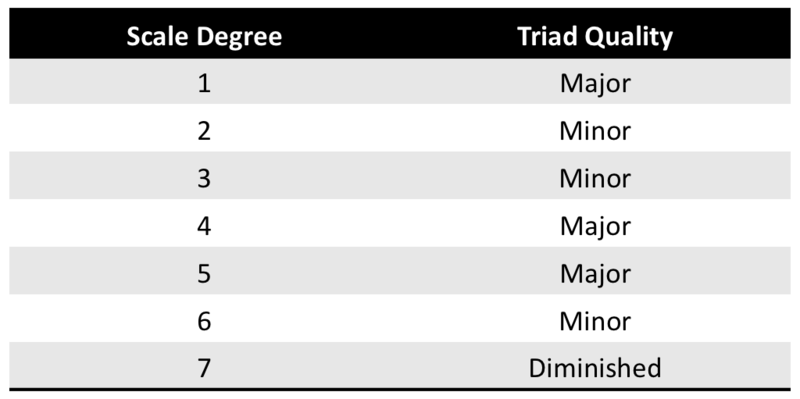

To avoid having to do that for every note in the scale, here's a handy chart:

Don't worry about diminished for now. Only weird people use that anyway.

So how do you feel? Honestly, if you've never encountered this stuff before and you understood everything here, then I'm very impressed. Actually I don't believe you. Regardless, like everything else, it takes a lot of repetition and practice to really get it. And even then, a lot of people really only master this stuff in a few keys. Sure, I could play you a 6-4-1-5 in F# major, but it'll take me a little longer to remember what chords to play. So don't worry if you don't immediately perfect this in every key. It's a lot to take in.

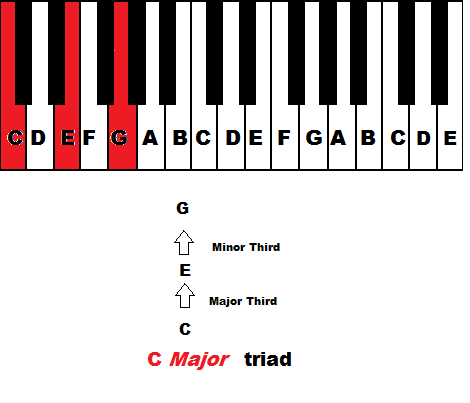

Triads

- A major triad contains an interval of a major third between the first and second notes and a minor third between the second and third notes (e.g., C-E-G)

- A minor triad contains an interval of a minor third between the root and second notes and a major third between the second and third notes(e.g., C-Eb-G)

- The major scale in any key consists of seven unique notes

- The intervals of the major scale, in order, are as follows:

- Whole Step

- Whole Step

- Half Step

- Whole Step

- Whole Step

- Whole Step

- Half Step

- Finally, because I'm still such a nice guy, I'm going to give you all twelve major scales in their most common spellings

C - D - E - F - G - A - B - C

Scales with flats:

F Major (1 flat)

F - G - A - Bb - C - D - E - F

Bb Major (2 flats)

Bb - C - D - Eb - F - G - A - Bb

Eb Major (3 flats)

Eb - F - G - Ab - Bb - C - D - Eb

Ab Major (4 flats)

Ab - Bb - C - Db - Eb - F - G - Ab

Db Major (5 flats)

Db - Eb - F - Gb - Ab - Bb - C - Db

Scales with sharps:

G Major (1 sharp)

G - A - B - C - D - E - F# - G

D Major (2 sharps)

D - E - F# - G - A - B - C# - D

A Major (3 sharps)

A - B - C# - D - E - F# - G# - A

E Major (4 sharps)

E - F# - G# - A - B - C# - D# - E

B Major (5 sharps)

B - C# - D# - E - F# - G# - A# - B

F# Major (6 sharps)

F# - G# - A# - B - C# - D# - E# - F#

Memorize all of that? Good. Because here comes the fun stuff.

Chords are created from thirds. However, the major scale consists of notes all separated by seconds. C to D is a second, D to E is a second, E to F is a second, and so on. Nevermind whether they are minor or major. Just know that they are all seconds.

C D E F G A B C

SECONDS

Since triads contain three notes separated by thirds, and not seconds, let's find a chord from the C major scale. And to make things easy, let's start on C. So what we do is start with our root (C), skip D, then go to our next note (E), skip the F, and then find our last note (G)

C __ E __ G

C-E-G? Why, that's a C major triad! And we got that by building a chord on the first scale degree. Go ahead, play it yourself (note: You can play the virtual keyboard using your computer keyboard. F and G on the computer play the notes F and G respectively, and everything else lines up accordingly. Try it out for yourself)

So what does this have to do with anything? Why are we making chords from scales? How will that help us play other people's songs or create or own?

Well, the big deal is that most songs with which we are familiar in Western culture are based around one key. That is to say that when an artist writes a song, most if not all of the notes in that song will belong to one key signature. If someone writes a song in the key of G, then probably at least 98% of the notes will be one of the following:

G A B C D E F# G

i.e., the notes of a G major scale.

The thing is, no one wants to hear all of those notes played at the same time. While the sequence of notes in a scale may sound good, playing them simultaneously will sound like garbage. Certain combinations of notes sound great together, and other combinations just suck. So to keep things under control within a song, we have harmony. Simply put, different sections of a song will be based around different chords. But whatever chord it is, it will likely be a chord that's consistent with the key signature. Take a listen to this song medley:

If you listen closely, you'll notice that the chord on the piano changes about every 2 seconds. The chords being played are as followed:

A minor: A - C - E

F major: F - A - C

C major: C - E - G

G major: G - B - D

The only major scale that contains all of these notes is C major. So we can probably assume - nay, I am TELLING YOU - that the songs in this medley are in the key of C!!.

The progression of A minor - F major - C major - G major is a 6-4-1-5 in the key of C. Remember, we created a C major chord by building a chord on the first scale degree of C major (i.e., the first note of the C major scale). That is the 1 in this progression. Let's double-check the others to make sure they're right.

6

What is the sixth scale degree of C major? Let's count up the scale:

C - 1

D - 2

E - 3

F - 4

G - 5

A - 6 BAM!

Now what do we get when we build a triad on that note?

A B C D E

A - C - E

A to C is a minor third. C to E is a major third. Which means the 6 chord of C major is an A minor triad!

4

What is the fourth scale degree of C major? Let's count up the scale:

C - 1

D - 2

E - 3

F - 4 SHAZAM!

Now what do we get when we build a triad on that note?

F G A B C

F - A - C

F to A is a major third. A to C is a minor third. Which means the 4 chord of C major is an F major triad!

5

What is the fifth scale degree of C major? Let's count up the scale:

C - 1

D - 2

E - 3

F - 4

G - 5 BAZINGA!

Now what do we get when we build a triad on that note?

G A B C D

G - B - D

G to B is a major third. B to D is a minor third. Which means the 5 chord of C major is a G major triad!

To avoid having to do that for every note in the scale, here's a handy chart:

Don't worry about diminished for now. Only weird people use that anyway.

So how do you feel? Honestly, if you've never encountered this stuff before and you understood everything here, then I'm very impressed. Actually I don't believe you. Regardless, like everything else, it takes a lot of repetition and practice to really get it. And even then, a lot of people really only master this stuff in a few keys. Sure, I could play you a 6-4-1-5 in F# major, but it'll take me a little longer to remember what chords to play. So don't worry if you don't immediately perfect this in every key. It's a lot to take in.

Tuesday, June 28, 2011

Lesson #4 - Scales (Major and Minor)

With chords discussed in a previous post eons ago, now would be a good time to delve into the two common types of scales.

Major Scales

If you've heard the Do-Re-Mi scale, then you already know what a major scale is, even if you haven't referred to it by that name before. For simplicity's sake, let's look at the notes of a C major scale:

C (Do)

D (Re)

E (Mi)

F (Fa)

G (So)

A (La)

B (Ti)

C (Do)

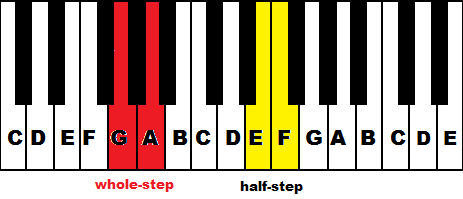

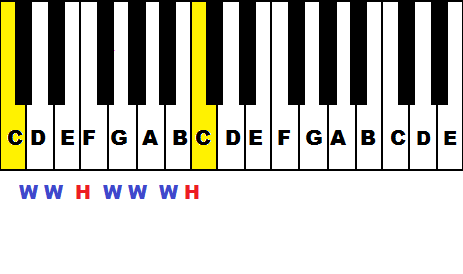

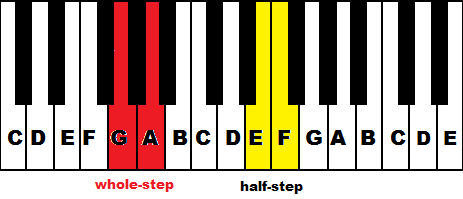

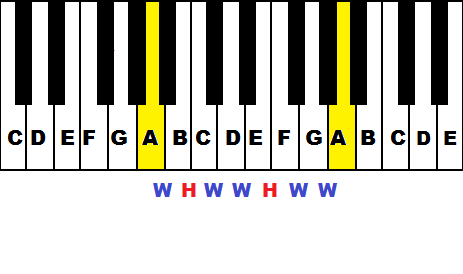

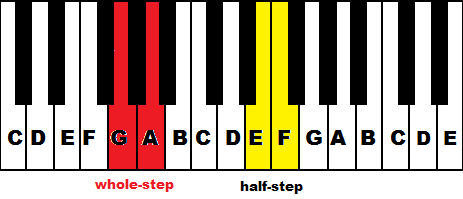

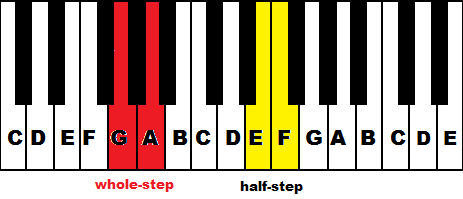

If you want to open up the Virtual Keyboard again and play those notes, you'll notice that the C scale consists of all white keys. Also remember the difference between whole steps and half-steps:

- The distance between two notes is a half step if there are no keys in between them (i.e., they're one semitone apart)

- The distance between two notes is a whole step if there is one key (either white or black) between them (i.e., they're two semitones apart)

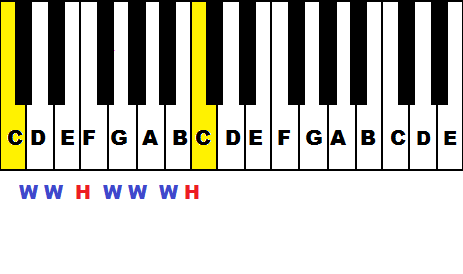

Therefore, the major scale consists of the following intervals:

Whole Step - Whole Step - Half Step - Whole Step - Whole Step - Whole Step - Half Step

But don't take my word for it. Take this picture's:

See that? The picture doesn't lie.

So what if you wanted to play the same type of scale, but starting on D? Well, grab your piano, keyboard, or Virtual Keyboard and play the following notes:

D E F# G A B C# D

Even though the notes are different from those of the C major scale, you can probably tell that the two scales sound very similar. That's because the intervals are the same from the first to last note. Because of this, you can change the root of any scale or chord, yet retain the same quality (i.e. minor stays minor, major stays major, etc) by moving all of the notes the same amount in the same direction!

Take, for example, the two major scales I just showed you. To transform a C major scale into a D major scale, simply look at the distance between the notes C and D. D is one whole step above C. Therefore, move every note of the C major scale up a whole step. Voila!

Minor Scales

Now that I've already gone over the major scale and changing keys, the rest shouldn't take long.

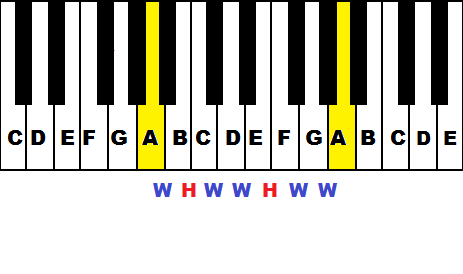

The formula for a minor scale is the following:

Whole Step - Half Step - Whole Step - Whole Step - Half Step - Whole Step - Whole Step

Now, which minor scale should I show you? To keep things simple, let's once again go with the one with all white keys. Is that C? Nope! It's A:

That's right! C major and A minor have the same notes! Which means that the two are related:

A is the relative minor of C

Likewise, C is the relative major of A

Play both scales and listen to how different they sound.

This handy nugget of information can save us a lot of time. If you want to learn all 12 major and minor scales, you can shorten the process by just remembering all of the major scales (still a lot of work, I know). Once you do that, you can figure out, for example, the G minor scale by doing the following:

- Count up 3 semitones from G. That gives us Bb

- Figure out what notes are in the Bb major scale (I'll help you out. It's Bb - C - D - Eb - F - G - A - Bb

- Play that very scale, but starting on G. Therefore, you'll be playing G - A - Bb - C - D - Eb - F - G

If you've never learned scales before, this is probably a lot to take in at once. Fortunately, there aren't really any tricks. All it takes is a lot of practice and repetition to let this stuff sink in.

Next lesson, I'll be getting to the good stuff. I keep mentioning the infamous 6-4-1-5 progression without explaining in too much detail what that means. For now, I'll just say that the numbers themselves refer partially to the scale degree of the major scale (i.e. the 6th note in a major scale, then the 4th note, then the 1st, then the 5th). See if you can figure out the rest before the next entry!

Major Scales

If you've heard the Do-Re-Mi scale, then you already know what a major scale is, even if you haven't referred to it by that name before. For simplicity's sake, let's look at the notes of a C major scale:

C (Do)

D (Re)

E (Mi)

F (Fa)

G (So)

A (La)

B (Ti)

C (Do)

If you want to open up the Virtual Keyboard again and play those notes, you'll notice that the C scale consists of all white keys. Also remember the difference between whole steps and half-steps:

- The distance between two notes is a half step if there are no keys in between them (i.e., they're one semitone apart)

- The distance between two notes is a whole step if there is one key (either white or black) between them (i.e., they're two semitones apart)

Therefore, the major scale consists of the following intervals:

Whole Step - Whole Step - Half Step - Whole Step - Whole Step - Whole Step - Half Step

But don't take my word for it. Take this picture's:

See that? The picture doesn't lie.

So what if you wanted to play the same type of scale, but starting on D? Well, grab your piano, keyboard, or Virtual Keyboard and play the following notes:

D E F# G A B C# D

Even though the notes are different from those of the C major scale, you can probably tell that the two scales sound very similar. That's because the intervals are the same from the first to last note. Because of this, you can change the root of any scale or chord, yet retain the same quality (i.e. minor stays minor, major stays major, etc) by moving all of the notes the same amount in the same direction!

Take, for example, the two major scales I just showed you. To transform a C major scale into a D major scale, simply look at the distance between the notes C and D. D is one whole step above C. Therefore, move every note of the C major scale up a whole step. Voila!

Minor Scales

Now that I've already gone over the major scale and changing keys, the rest shouldn't take long.

The formula for a minor scale is the following:

Whole Step - Half Step - Whole Step - Whole Step - Half Step - Whole Step - Whole Step

Now, which minor scale should I show you? To keep things simple, let's once again go with the one with all white keys. Is that C? Nope! It's A:

That's right! C major and A minor have the same notes! Which means that the two are related:

A is the relative minor of C

Likewise, C is the relative major of A

Play both scales and listen to how different they sound.

This handy nugget of information can save us a lot of time. If you want to learn all 12 major and minor scales, you can shorten the process by just remembering all of the major scales (still a lot of work, I know). Once you do that, you can figure out, for example, the G minor scale by doing the following:

- Count up 3 semitones from G. That gives us Bb

- Figure out what notes are in the Bb major scale (I'll help you out. It's Bb - C - D - Eb - F - G - A - Bb

- Play that very scale, but starting on G. Therefore, you'll be playing G - A - Bb - C - D - Eb - F - G

If you've never learned scales before, this is probably a lot to take in at once. Fortunately, there aren't really any tricks. All it takes is a lot of practice and repetition to let this stuff sink in.

Next lesson, I'll be getting to the good stuff. I keep mentioning the infamous 6-4-1-5 progression without explaining in too much detail what that means. For now, I'll just say that the numbers themselves refer partially to the scale degree of the major scale (i.e. the 6th note in a major scale, then the 4th note, then the 1st, then the 5th). See if you can figure out the rest before the next entry!

My Own 4 Chords Medley

No matter how many of these are done, we're never going to pinpoint every single song that uses a 6-4-1-5 (or 1-5-6-4) progression. More on what this actually means in another post. But for now, enjoy the 13 (ish?) tune mashup ala Axis of Awesome!

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

Lesson #3 - Chords (Major and Minor Triads)

Because major and minor chords make up about 80% of pop music. Everything else can be seen as slight additions/revisions to those chords. For now, I'll discuss major and minor triads, which are 3-note chords.

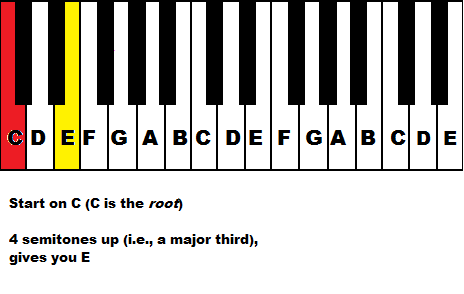

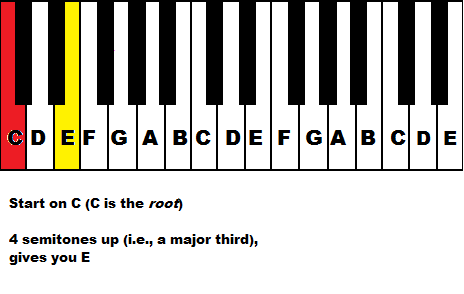

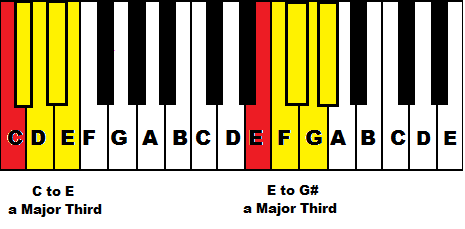

Major Triads

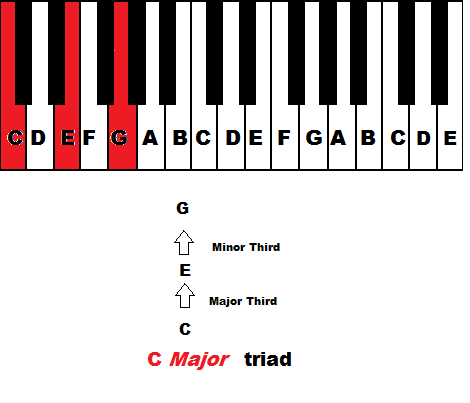

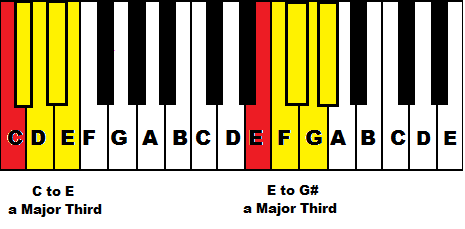

Remember major 3rd and minor 3rd intervals? You better, because those are essentially the foundation of chord structures. To form a major triad on any one note (for example, C), we first go up a major third from the root. C is the root, so going up a major third gives you E

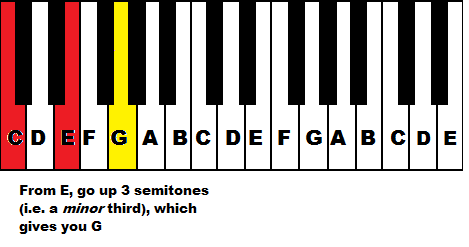

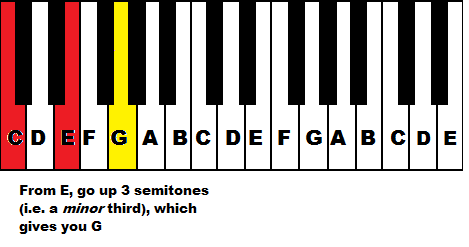

That covers two notes of the triad. To get the last note, start on the second note (the E in this case), and go up a minor third

In conclusion:

As always, I encourage you to play out the notes so you can hear what the chords sound like. You can play multiple notes at one time using this virtual keyboard.

Since I'm such a nice guy, rather than making you figure out each major chord on your own, I'll just list them out. The first note of each triad is the name of the chord (e.g., F A C is an F major triad). Also remember that black keys can have two different note names (e.g., Bb and A# are the same, as is D# and Eb).

C E G

F A C

Bb D F

Eb G Bb

Ab C Eb

Db F Ab

F# A# C#

B D# F#

E G# B

A C# E

D F# A

G B D

________________________________________________________________

Got all that? I hope so. Because now it's time for minor triads!

________________________________________________________________

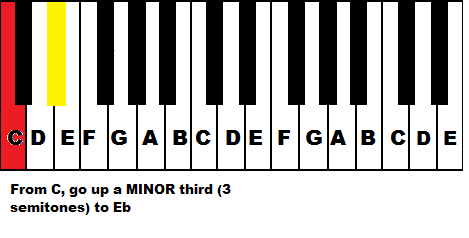

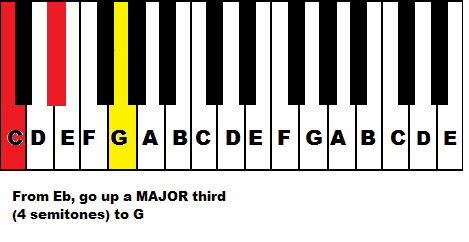

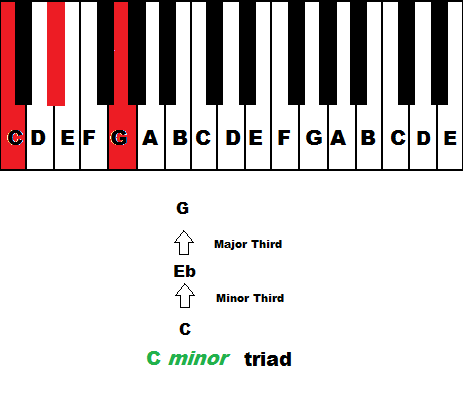

Minor Triads

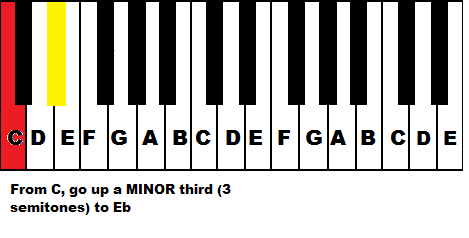

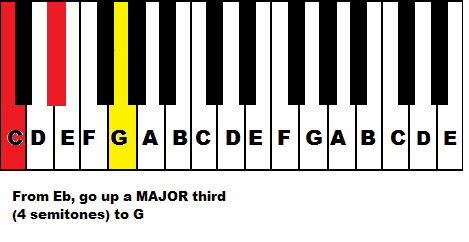

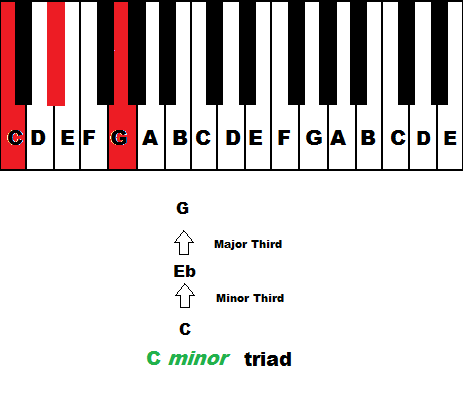

There are a few ways in which you can think about minor triads. The "proper" way is to think about the intervals. Whereas a major triad contains a major third, and THEN a minor, a minor triad is the opposite. A minor triad starts with a minor third and ends with a major third.

In a nutshell:

If you're particularly observant, you might have noticed that 2 out of the 3 notes of a major and minor chord are the same. The root (in this case, C) and the fifth (G) are the same in both major and minor. However, the third is E in a C major triad, but Eb in minor. In other words, the third of a minor chord is one semitone lower than the third of a major. This little trick may help you remember minor chords more easily if you don't want to go through the hassle of calculating those intervals every time.

But for your convenience, I'll list out all of the minor triads just like I did with major:

C Eb G

F Ab C

Bb Db F

Eb Gb Bb

Ab B Eb **

Db E Ab **

F# A C#

B D F#

E G B

A C E

D F A

G Bb D

** Pure music theorists would argue that the proper spellings for these chords should contain Cb instead of B, and Fb instead of E. Ignore them. Just use B and E. It's a lot easier.

Rather than add even more to this excruciatingly long entry, I'll provide an example of how these chords are used in a separate post. Stay tuned!

Major Triads

Remember major 3rd and minor 3rd intervals? You better, because those are essentially the foundation of chord structures. To form a major triad on any one note (for example, C), we first go up a major third from the root. C is the root, so going up a major third gives you E

That covers two notes of the triad. To get the last note, start on the second note (the E in this case), and go up a minor third

In conclusion:

As always, I encourage you to play out the notes so you can hear what the chords sound like. You can play multiple notes at one time using this virtual keyboard.

Since I'm such a nice guy, rather than making you figure out each major chord on your own, I'll just list them out. The first note of each triad is the name of the chord (e.g., F A C is an F major triad). Also remember that black keys can have two different note names (e.g., Bb and A# are the same, as is D# and Eb).

C E G

F A C

Bb D F

Eb G Bb

Ab C Eb

Db F Ab

F# A# C#

B D# F#

E G# B

A C# E

D F# A

G B D

________________________________________________________________

Got all that? I hope so. Because now it's time for minor triads!

________________________________________________________________

Minor Triads

There are a few ways in which you can think about minor triads. The "proper" way is to think about the intervals. Whereas a major triad contains a major third, and THEN a minor, a minor triad is the opposite. A minor triad starts with a minor third and ends with a major third.

In a nutshell:

If you're particularly observant, you might have noticed that 2 out of the 3 notes of a major and minor chord are the same. The root (in this case, C) and the fifth (G) are the same in both major and minor. However, the third is E in a C major triad, but Eb in minor. In other words, the third of a minor chord is one semitone lower than the third of a major. This little trick may help you remember minor chords more easily if you don't want to go through the hassle of calculating those intervals every time.

But for your convenience, I'll list out all of the minor triads just like I did with major:

C Eb G

F Ab C

Bb Db F

Eb Gb Bb

Ab B Eb **

Db E Ab **

F# A C#

B D F#

E G B

A C E

D F A

G Bb D

** Pure music theorists would argue that the proper spellings for these chords should contain Cb instead of B, and Fb instead of E. Ignore them. Just use B and E. It's a lot easier.

Rather than add even more to this excruciatingly long entry, I'll provide an example of how these chords are used in a separate post. Stay tuned!

Monday, March 7, 2011

Lesson #2 - Intervals

If you've hung around musical people before, you might have heard someone talk about "thirds," "fourths" or "fifths." These people are talking about intervals, a musical concept that can seem rather intimidating unless someone explains them to you. And that's exactly what I'm going to do!

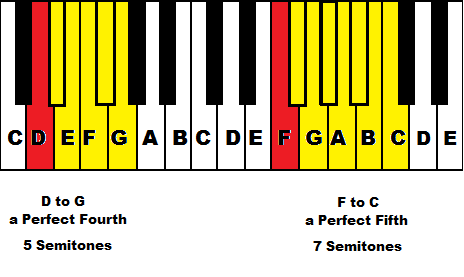

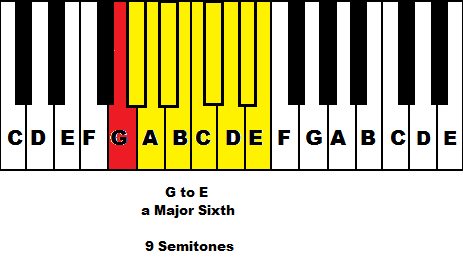

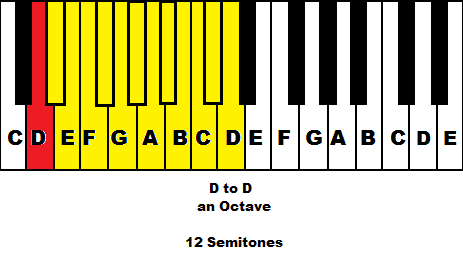

You may recall me mentioning that the distance between any two consecutive notes on the piano is called a semitone. A semitone, also called a half-step, is just an interval, and every other interval is measured by its number of semitones. Before I explain this further, here's a list of all the intervals you will need to know:

1 Semitone - Minor Second

2 Semitones - Major Second

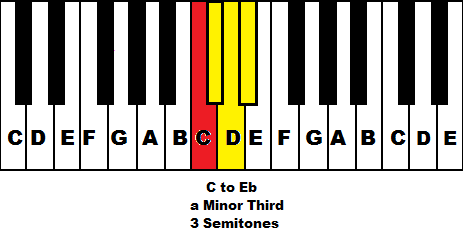

**3 Semitones - Minor Third**

**4 Semitones - Major Third**

**5 Semitones - Perfect Fourth**

6 Semitones - Tritone

**7 Semitones - Perfect Fifth**

8 Semitones - Minor Sixth

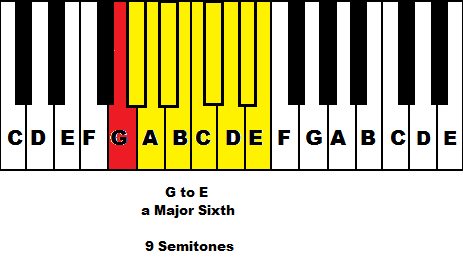

**9 Semitones - Major Sixth**

10 Semitones - Minor Seventh

11 Semitones - Major Seventh

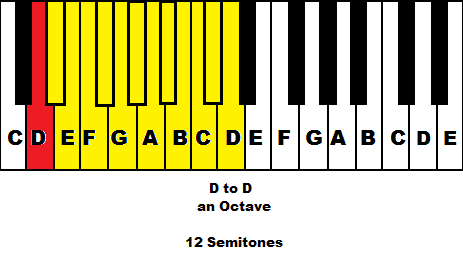

**12 Semitones - Octave**

I've starred and bolded the ones that are important for now. Let's go over each of these individually:

Major Third

Remember that a major third is 4 semitones away from the starting note. C to E is a major third, and so is E to G# (because of the funky pairs of B/C and E/F).

Don't forget about the useful Virtual Keyboard so you can play the notes yourself to see what these intervals sound like.

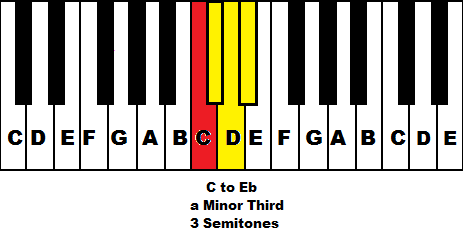

Minor Third

I decided to cover minor thirds after major thirds just because people generally cover major before minor when they learn music. Regardless, the concept is similar.

Minor thirds are 3 semitones away from their root notes. An Eb is 3 semitones above a C.

***Useful note: This will come up in the next lesson, but the third is the foundation of pretty much all chords. For example, a C chord is a C, a major third from C (which is E), and a minor third from E (which is G). Basically, if you can do thirds, you can do chords!**

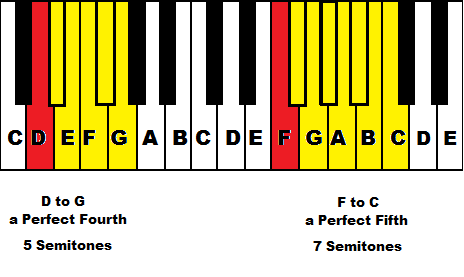

Perfect Fourth and Fifths

Fourths and Fifths are a little different. Unlike other intervals, fourths and fifths can never be major or minor, but cam only be perfect, augmented or diminished. Perfect fourths and fifth are the more commons ones, so let's just focus on those. As you can see, a note is a perfect fourth if it's 5 semitones away from the starting note and a perfect fifth if it's 7 semitones away.

Major Sixth

Self-explanatory at this point. 9 semitones will give you a major sixth.

Octave

You can remember that an octave is 12 semitones, but the easiest way to remember is just that an octave is just the next instance of the same note on the piano (e.g., an octave from G is the next closest G in either direction).

There are a few other things I should note:

- The same interval from the same note in opposite directions will NOT yield the same pitch class. For example, a major sixth UP from C is an A, but a major sixth DOWN from C is an Eb.

- On the same note, in order to get to the same note going in one direction as the other, all you need to do is invert the interval and the quality. Here's what I mean:

If you go up a major sixth from C, you get an A. If you want to go DOWN to A from C, you invert the major sixth. To invert an interval, you subtract the number from 9 and invert the quality. Major and minor are inverses of each other, as are diminished and augmented (not covered here). Perfect stays perfect.

So, to invert the major sixth, major becomes minor, and then you subtract 6 from 9 (9 - 6 = 3). Therefore, the inverse of a major sixth is a minor third. In other words, going up a major sixth from C will yield the same pitch class as going down a minor third from C (A).

- Intervals from a minor second to an octave are simple intervals. Intervals above that are called compound intervals. To get the corresponding simple interval from a compound, simply subtract 7. For example, A major ninth is essentially the same thing as a major second (just separated by an additional octave).

Remember these intervals and simple tips, practice with them on a piano or the online keyboard, and you'll be able to not only play, but understand chords.

Next lesson: *guess what it is. Go on, guess*

CHORDS!!

You may recall me mentioning that the distance between any two consecutive notes on the piano is called a semitone. A semitone, also called a half-step, is just an interval, and every other interval is measured by its number of semitones. Before I explain this further, here's a list of all the intervals you will need to know:

1 Semitone - Minor Second

2 Semitones - Major Second

**3 Semitones - Minor Third**

**4 Semitones - Major Third**

**5 Semitones - Perfect Fourth**

6 Semitones - Tritone

**7 Semitones - Perfect Fifth**

8 Semitones - Minor Sixth

**9 Semitones - Major Sixth**

10 Semitones - Minor Seventh

11 Semitones - Major Seventh

**12 Semitones - Octave**

I've starred and bolded the ones that are important for now. Let's go over each of these individually:

Major Third

Remember that a major third is 4 semitones away from the starting note. C to E is a major third, and so is E to G# (because of the funky pairs of B/C and E/F).

Don't forget about the useful Virtual Keyboard so you can play the notes yourself to see what these intervals sound like.

Minor Third

I decided to cover minor thirds after major thirds just because people generally cover major before minor when they learn music. Regardless, the concept is similar.

Minor thirds are 3 semitones away from their root notes. An Eb is 3 semitones above a C.

***Useful note: This will come up in the next lesson, but the third is the foundation of pretty much all chords. For example, a C chord is a C, a major third from C (which is E), and a minor third from E (which is G). Basically, if you can do thirds, you can do chords!**

Perfect Fourth and Fifths

Fourths and Fifths are a little different. Unlike other intervals, fourths and fifths can never be major or minor, but cam only be perfect, augmented or diminished. Perfect fourths and fifth are the more commons ones, so let's just focus on those. As you can see, a note is a perfect fourth if it's 5 semitones away from the starting note and a perfect fifth if it's 7 semitones away.

Major Sixth

Self-explanatory at this point. 9 semitones will give you a major sixth.

Octave

You can remember that an octave is 12 semitones, but the easiest way to remember is just that an octave is just the next instance of the same note on the piano (e.g., an octave from G is the next closest G in either direction).

There are a few other things I should note:

- The same interval from the same note in opposite directions will NOT yield the same pitch class. For example, a major sixth UP from C is an A, but a major sixth DOWN from C is an Eb.

- On the same note, in order to get to the same note going in one direction as the other, all you need to do is invert the interval and the quality. Here's what I mean:

If you go up a major sixth from C, you get an A. If you want to go DOWN to A from C, you invert the major sixth. To invert an interval, you subtract the number from 9 and invert the quality. Major and minor are inverses of each other, as are diminished and augmented (not covered here). Perfect stays perfect.

So, to invert the major sixth, major becomes minor, and then you subtract 6 from 9 (9 - 6 = 3). Therefore, the inverse of a major sixth is a minor third. In other words, going up a major sixth from C will yield the same pitch class as going down a minor third from C (A).

- Intervals from a minor second to an octave are simple intervals. Intervals above that are called compound intervals. To get the corresponding simple interval from a compound, simply subtract 7. For example, A major ninth is essentially the same thing as a major second (just separated by an additional octave).

Remember these intervals and simple tips, practice with them on a piano or the online keyboard, and you'll be able to not only play, but understand chords.

Next lesson: *guess what it is. Go on, guess*

CHORDS!!

Saturday, February 12, 2011

Michael Jackson Cover!

No, I didn't do "Beat It" or "Billie Jean" or anything like that. I first heard "Hold My Hand" on the radio back in October, and I kind of liked it. Then, as with many other songs, I heard it more, and I liked it more. Then I heard it even more, and I REALLY liked it. You can see where I'm going with this.

I haven't done an a cappella cover since "Nothing On You" by B.O.B. back in June, so this one was a lot of fun to do!

So here it is. The result of multi-track layerings of my voice + a one-day Flipcam rental + amazing audio and video editing software + 2-3 hours of work per day over 4 days:

I haven't done an a cappella cover since "Nothing On You" by B.O.B. back in June, so this one was a lot of fun to do!

So here it is. The result of multi-track layerings of my voice + a one-day Flipcam rental + amazing audio and video editing software + 2-3 hours of work per day over 4 days:

Thursday, February 10, 2011

Lesson #1 - The Musical Alphabet

Welcome class! Today you will begin a wondrous journey into the cross-cultural, universal language known as music. Judging by the title of this post, you can probably deduce that this particular lesson is not intended for people with a fair amount of musical background. No sir, this is for people who look at a piano and tilt their heads in utter confusion.

So anyway, the musical alphabet is relatively simple. Do you know the English alphabet? You know, A though Z? Congrats! You already know over half of the musical alphabet (in terms of actual pitches. I'll explain that in a bit). The musical alphabet uses the following letters:

A B C D E F G

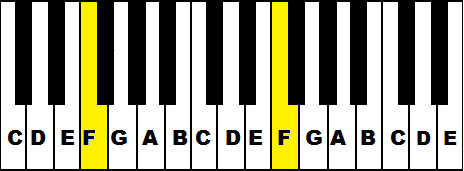

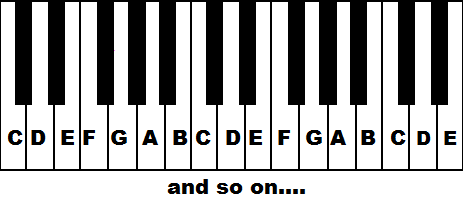

Simple, no? Let's take a look at that on the piano:

As you can see, once you get to G, you don't move up to H, nor do you start moving backwards. You simple go back to A. Because of this, think of these 7 notes of the musical alphabet more circularly rather than linearly. B is higher than A and lower than C. F is higher than E and lower than G. And G is higher than F, but lower than the next A. Two notes with the same name (e.g., two C's) but located at different places on the piano are said to be in different octaves.

Try this on a piano (if you don't have a piano or keyboard near you, use this). Play a few random notes on the piano. Take note of how different they sound. Now play the same note in different octaves (e.g., play an F, then play another F in a different spot). Even though one is higher than the other, the two sound pretty similar, don't they? That's what an octave essentially is.

**Scientifically/mathematically/nerdily speaking, if note X is an octave above note Y, then the frequency of note X is twice that of note Y (which means that the frequency of note Y is half that of note X). Remember, notes are just sound waves, which means that molecules in the air are vibrating at a certain rate. If I've lost you, then don't worry about it. It's not important for our purposes.

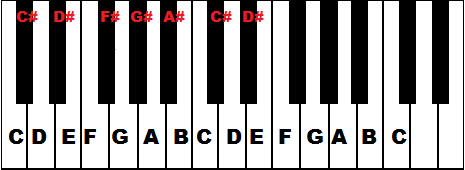

Now that you've got a hang of the initial 7 notes, let's figure out what those black keys are:

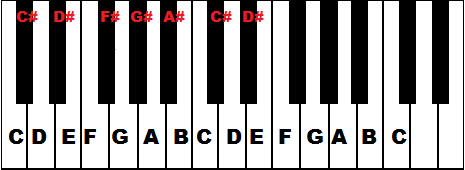

Ignoring the immaculate precision of MS Paint placing the notes on the keys, notice those strange symbols. What does that "#" sign mean? "C number? F number?"

'#' means 'sharp.' The black key immediately to the right of C is C#, to the right of D is D#, and so on. As you can probably guess, C# is sonically between C and D, hence the location of the black keys on the piano.

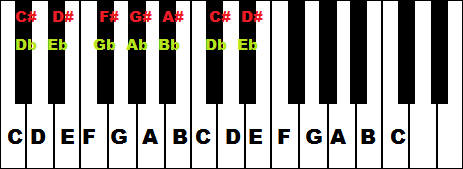

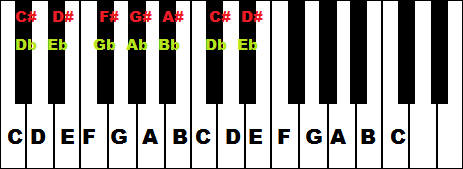

But wait! There's more!!

Oh great, now there's uppercase AND lowercase B's? Don't worry, the lowercase 'b' on the black keys means "flat." Whereas a sharp sign (#) means to raise the pitch by a half-step, a flat sign (b) means to lower the pitch of a note by half a step.

WHICH MEANS that 'C#' is the same thing as 'Db' (from a practical standpoint, not from a music theorist's perspective. We'll only worry about the practical).

"Hold on!" says you. "I see a flaw in your little theory. There's no black key between E and F, nor is there one between B and C! Explain that!!"

Well spotted, my young Padawan. Unfortunately for us, the musical deities at be had to make things rather complicated for us. The distance between any two consecutive notes on a piano (do NOT count two white keys as consecutive if there's a black key between them. Duh) is half-step, also called a semitone. Which means that the distance between two white keys is usually two semitones/two half-steps/one whole step. But the distance between E and F, as well as the distance between B and C, is only one semitone.

Whoops! Time to run to class! That's all for today. More to come eventually!

So anyway, the musical alphabet is relatively simple. Do you know the English alphabet? You know, A though Z? Congrats! You already know over half of the musical alphabet (in terms of actual pitches. I'll explain that in a bit). The musical alphabet uses the following letters:

A B C D E F G

Simple, no? Let's take a look at that on the piano:

As you can see, once you get to G, you don't move up to H, nor do you start moving backwards. You simple go back to A. Because of this, think of these 7 notes of the musical alphabet more circularly rather than linearly. B is higher than A and lower than C. F is higher than E and lower than G. And G is higher than F, but lower than the next A. Two notes with the same name (e.g., two C's) but located at different places on the piano are said to be in different octaves.

Try this on a piano (if you don't have a piano or keyboard near you, use this). Play a few random notes on the piano. Take note of how different they sound. Now play the same note in different octaves (e.g., play an F, then play another F in a different spot). Even though one is higher than the other, the two sound pretty similar, don't they? That's what an octave essentially is.

**Scientifically/mathematically/nerdily speaking, if note X is an octave above note Y, then the frequency of note X is twice that of note Y (which means that the frequency of note Y is half that of note X). Remember, notes are just sound waves, which means that molecules in the air are vibrating at a certain rate. If I've lost you, then don't worry about it. It's not important for our purposes.

Now that you've got a hang of the initial 7 notes, let's figure out what those black keys are:

Ignoring the immaculate precision of MS Paint placing the notes on the keys, notice those strange symbols. What does that "#" sign mean? "C number? F number?"

'#' means 'sharp.' The black key immediately to the right of C is C#, to the right of D is D#, and so on. As you can probably guess, C# is sonically between C and D, hence the location of the black keys on the piano.

But wait! There's more!!

Oh great, now there's uppercase AND lowercase B's? Don't worry, the lowercase 'b' on the black keys means "flat." Whereas a sharp sign (#) means to raise the pitch by a half-step, a flat sign (b) means to lower the pitch of a note by half a step.

WHICH MEANS that 'C#' is the same thing as 'Db' (from a practical standpoint, not from a music theorist's perspective. We'll only worry about the practical).

"Hold on!" says you. "I see a flaw in your little theory. There's no black key between E and F, nor is there one between B and C! Explain that!!"

Well spotted, my young Padawan. Unfortunately for us, the musical deities at be had to make things rather complicated for us. The distance between any two consecutive notes on a piano (do NOT count two white keys as consecutive if there's a black key between them. Duh) is half-step, also called a semitone. Which means that the distance between two white keys is usually two semitones/two half-steps/one whole step. But the distance between E and F, as well as the distance between B and C, is only one semitone.

Whoops! Time to run to class! That's all for today. More to come eventually!

Tuesday, February 1, 2011

Lessons For Beginners?

So for the longest time, I've been thinking about starting some series of lectures, videos, or articles with lessons for those who are new to music but want to learn. Why do I want to do this?

Suppose you ask your friend to teach you how to play the chords to a song on the guitar or piano. For example, "Apologize" by One Republic. Your friend says, "Oh that's an easy one. It's just 6-4-1-5 in Eb major."

If you a have a basic knowledge of music theory, then you probably understand what this means. You may also be pleased to know that your friend just gave you the formula for almost every successful pop song in the last 40 years.

However, if this confuses you, then your friend would probably say something like, "Just repeat C minor - Ab major - Eb major - Bb major over and over again."

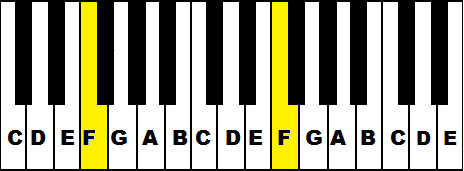

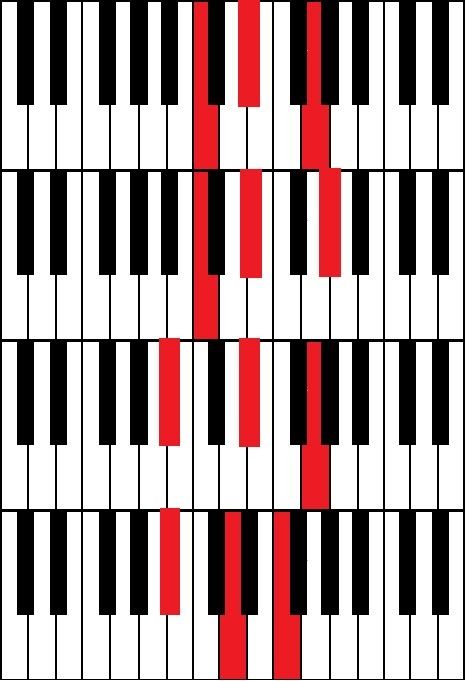

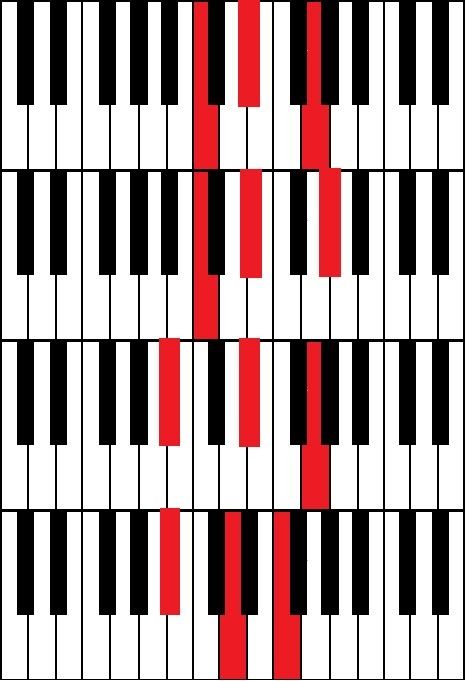

Maybe now you're not as baffled. Maybe you're more perplexed than ever. If the latter is true, then maybe your friend shows you the exact keys on the piano:

There you go. Crystal clear! Delighting in the new addition to your musical repertoire, you play Apologize non-stop for about a week until you get bored with it. You then find your friend again and ask the following:

"Dude, can you teach me how to play 'Beautiful' by Akon?"

Your friend smacks his hand to his face. Any guesses why?

Probably because you essentially already know how to play that song. You just don't realize it.

And that, dear readers, is what I hope to provide. A basic understanding of how to read and understand music in the context of music that you like. I plan to provide a series of lessons of how to not only play some of your favorite songs, but how to understand what your playing and therefore learn other song much more easily.

In the meantime, here are some of my favorite music-related websites:

MusicTheory.net A huge list of comprehensive general music lessons and exercises

Virtual Keyboard Unless most other online pianos, you can actually use the keys on your computer keyboard to play the notes.

BPM Tracker Want to figure out the tempo of a song? Just tap a key on your keyboard to the beat of the song, and this nifty tool will calculate it for you.

I'll be back soon with another post, either my first lesson or something completely unrelated. In the meantime, here's something to pique your interest:

Suppose you ask your friend to teach you how to play the chords to a song on the guitar or piano. For example, "Apologize" by One Republic. Your friend says, "Oh that's an easy one. It's just 6-4-1-5 in Eb major."

If you a have a basic knowledge of music theory, then you probably understand what this means. You may also be pleased to know that your friend just gave you the formula for almost every successful pop song in the last 40 years.

However, if this confuses you, then your friend would probably say something like, "Just repeat C minor - Ab major - Eb major - Bb major over and over again."

Maybe now you're not as baffled. Maybe you're more perplexed than ever. If the latter is true, then maybe your friend shows you the exact keys on the piano:

There you go. Crystal clear! Delighting in the new addition to your musical repertoire, you play Apologize non-stop for about a week until you get bored with it. You then find your friend again and ask the following:

"Dude, can you teach me how to play 'Beautiful' by Akon?"

Your friend smacks his hand to his face. Any guesses why?

Probably because you essentially already know how to play that song. You just don't realize it.

And that, dear readers, is what I hope to provide. A basic understanding of how to read and understand music in the context of music that you like. I plan to provide a series of lessons of how to not only play some of your favorite songs, but how to understand what your playing and therefore learn other song much more easily.

In the meantime, here are some of my favorite music-related websites:

MusicTheory.net A huge list of comprehensive general music lessons and exercises

Virtual Keyboard Unless most other online pianos, you can actually use the keys on your computer keyboard to play the notes.

BPM Tracker Want to figure out the tempo of a song? Just tap a key on your keyboard to the beat of the song, and this nifty tool will calculate it for you.

I'll be back soon with another post, either my first lesson or something completely unrelated. In the meantime, here's something to pique your interest:

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Country? Wtf?

Yup, my next cover is a country song. If you know me well, you know I'm not too fond of country music overall. Well then, why did I choose to cover "I Won't Let Go" by Rascal Flatts? If you're curious, continue reading. If you want to just watch the video, skip to the bottom of this post. If you care about neither the backstory nor the video, then why the hell are you reading this in the first place?

Anyway I am in an a cappella group called the New Dominions. These people sing. And make drum sounds with their mouths. And tell very weird jokes. And are very odd people in general.

Which is why I love them.

That, and one of the songs we're performing this semester is this very song. Since I was going to be forced to take part in this one way or another, I figured I'd listen to the song ahead of time just to see what it's like. And you know what? It's pretty damn good!

When I think of country, I think of bluegrass "Weeeel ah waz born een Texas in mah daddeh's pick up truuuuuuuuck...." Nah, this song's more of a ballad. You could easily replace the lead singer with Luther Vandross or Brian McKnight and pass it off as a 90's R&B hit.

Anyway, I and every other guy in the New Dos auditioned for the solo for this song. Alas, I did not get it likely due to any or all of the following reasons:

1. The song is very high and out of my range.

2. There are plenty of better singers in the group

3. My voice has a bit of a raspy quality to it, not ideally suited for power ballads or anything like them.

So since I love this song so much, I resorted to my default option for any song that gets stuck in my head: make a YouTube cover. Doing my own version would also alleviate the problems that plagued me during my audition:

1. I can now lower the key and sing it in a more comfortable range.

2. I don't have to compete with other singers.

3. Yes, my voice is still raspy. F%$# it; it's my channel and I'll sing a country ballad if I want to!

Anyway, enjoy:

Anyway I am in an a cappella group called the New Dominions. These people sing. And make drum sounds with their mouths. And tell very weird jokes. And are very odd people in general.

Which is why I love them.

That, and one of the songs we're performing this semester is this very song. Since I was going to be forced to take part in this one way or another, I figured I'd listen to the song ahead of time just to see what it's like. And you know what? It's pretty damn good!

When I think of country, I think of bluegrass "Weeeel ah waz born een Texas in mah daddeh's pick up truuuuuuuuck...." Nah, this song's more of a ballad. You could easily replace the lead singer with Luther Vandross or Brian McKnight and pass it off as a 90's R&B hit.

Anyway, I and every other guy in the New Dos auditioned for the solo for this song. Alas, I did not get it likely due to any or all of the following reasons:

1. The song is very high and out of my range.

2. There are plenty of better singers in the group

3. My voice has a bit of a raspy quality to it, not ideally suited for power ballads or anything like them.

So since I love this song so much, I resorted to my default option for any song that gets stuck in my head: make a YouTube cover. Doing my own version would also alleviate the problems that plagued me during my audition:

1. I can now lower the key and sing it in a more comfortable range.

2. I don't have to compete with other singers.

3. Yes, my voice is still raspy. F%$# it; it's my channel and I'll sing a country ballad if I want to!

Anyway, enjoy:

Saturday, January 22, 2011

Welcome to Blogging!

Okay, so this isn't my first attempt at blogging. I had a blog a few years ago for something else entirely, but I'll get to that in a moment.

So, what can you expect to find here? In order to give you a better idea, I should probably get into a few details about who I am:

1) I am a college senior, tentatively set to work at a software company after I graduate in May.

2) I like to dabble in music. By that I mean that I am/was a member of two different a cappella groups, I play tenor saxophone in a small jazz combo, and I am self-taught in a small amount of piano and guitar.

3) I'm a big fan of NBA basketball. I've been a Lakers fan since I was a child (I can already hear the moans of disdain), but I appreciate all of the great players in the league. Others sports...well, I'll watch them if others around me are, and I have a small amount of knowledge about the NFL and professional tennis players. College sports, I got nothing.

4) I've been into making YouTube videos off and on since high school. What kind of videos? Why, I'm glad you asked:

I'll talk about my second channel first, seeing as the back story behind it is much shorter than of my first one, and because it's the one that I still work on.

When I say that I dabble in music, I usually mean other people's music. I've written a few of my own songs, but it's so much easier to perform stuff that's already out there. So, about a year ago, I bought myself an iMac and pursued a new hobby. I would follow in the footsteps of many musicians both talented and talentless and create covers of popular songs for the sole purpose of putting them on YouTube. Why not? I had a computer, a keyboard, knowledge of the difference between major and minor chords, huge delusions of grandeur, and the ability to casually strum more than 3 different chords on the guitar. Clearly that's all it takes to become famous (am I right, Justin Bieber?).

My first cover was of “Down” by Jay Sean. I rustled up a honky, 4-instrument version of it that took me 2 hours max to do on Garageband, put one of those stock iMovie title screens behind it, uploaded it to my new channel, and waited for the record labels to start calling me. But when a week past without any sign of an upcoming multi-billion dollar recording contract, I was devastated. Oh well, just gotta keep trying, I said. Not everything on that damn site goes viral after all.

Over the next few months I learned quite a bit from subscribing to (i.e. stalking) other YouTube musicians. For one, if you use better recording equipment than just the internal mic on your computer, you'll sound so much better. Eureka! Also, there's better software out there than Garageband. Holy crap! What's more, making actual videos to go along with your music instead of still pictures can make the entire experience more exciting. Well I'll be damned!

I went through a long stretch of time without making any videos, but I'd like to think that my past few covers since then have shown a fair amount of improvement both musically and visually. Though I've pretty much conceded that I'm neither good enough nor lucky enough to become famous off of clips of me singing Mika songs into a webcam.

But Kiran, you ask, why continue making YouTube song videos?

Because it's fun!

I'm in my last semester of college and am pretty much free from all major responsibilities besides merely passing my classes. Why not make random music and show it off online? There are far less productive ways to use your free time. Right now I'm working on a few projects with some friends and just continuing to cover songs on my own. I'm not expecting nor wishing for a record deal to come out of this. I do it merely for the sake of artistic expression and creativity...or something like that.

You can click the link to my YouTube channel on the side or click here. I'll be updating this blog with new video releases, plus whatever random crap I feel like talking about at the time.

In the interest of my fellow reader(s)'s short attention spans, I'll separate the details of my other, former channel into a different post.

So, what can you expect to find here? In order to give you a better idea, I should probably get into a few details about who I am:

1) I am a college senior, tentatively set to work at a software company after I graduate in May.

2) I like to dabble in music. By that I mean that I am/was a member of two different a cappella groups, I play tenor saxophone in a small jazz combo, and I am self-taught in a small amount of piano and guitar.

3) I'm a big fan of NBA basketball. I've been a Lakers fan since I was a child (I can already hear the moans of disdain), but I appreciate all of the great players in the league. Others sports...well, I'll watch them if others around me are, and I have a small amount of knowledge about the NFL and professional tennis players. College sports, I got nothing.

4) I've been into making YouTube videos off and on since high school. What kind of videos? Why, I'm glad you asked:

I'll talk about my second channel first, seeing as the back story behind it is much shorter than of my first one, and because it's the one that I still work on.

When I say that I dabble in music, I usually mean other people's music. I've written a few of my own songs, but it's so much easier to perform stuff that's already out there. So, about a year ago, I bought myself an iMac and pursued a new hobby. I would follow in the footsteps of many musicians both talented and talentless and create covers of popular songs for the sole purpose of putting them on YouTube. Why not? I had a computer, a keyboard, knowledge of the difference between major and minor chords, huge delusions of grandeur, and the ability to casually strum more than 3 different chords on the guitar. Clearly that's all it takes to become famous (am I right, Justin Bieber?).

My first cover was of “Down” by Jay Sean. I rustled up a honky, 4-instrument version of it that took me 2 hours max to do on Garageband, put one of those stock iMovie title screens behind it, uploaded it to my new channel, and waited for the record labels to start calling me. But when a week past without any sign of an upcoming multi-billion dollar recording contract, I was devastated. Oh well, just gotta keep trying, I said. Not everything on that damn site goes viral after all.

Over the next few months I learned quite a bit from subscribing to (i.e. stalking) other YouTube musicians. For one, if you use better recording equipment than just the internal mic on your computer, you'll sound so much better. Eureka! Also, there's better software out there than Garageband. Holy crap! What's more, making actual videos to go along with your music instead of still pictures can make the entire experience more exciting. Well I'll be damned!

I went through a long stretch of time without making any videos, but I'd like to think that my past few covers since then have shown a fair amount of improvement both musically and visually. Though I've pretty much conceded that I'm neither good enough nor lucky enough to become famous off of clips of me singing Mika songs into a webcam.

But Kiran, you ask, why continue making YouTube song videos?

Because it's fun!

I'm in my last semester of college and am pretty much free from all major responsibilities besides merely passing my classes. Why not make random music and show it off online? There are far less productive ways to use your free time. Right now I'm working on a few projects with some friends and just continuing to cover songs on my own. I'm not expecting nor wishing for a record deal to come out of this. I do it merely for the sake of artistic expression and creativity...or something like that.

You can click the link to my YouTube channel on the side or click here. I'll be updating this blog with new video releases, plus whatever random crap I feel like talking about at the time.

In the interest of my fellow reader(s)'s short attention spans, I'll separate the details of my other, former channel into a different post.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)